By Robbie LaFleur

Textile Conservator and Weavers Guild member Beth McLaughlin gave generously of her time this month to introduce Phyllis Waggoner and me to her fascinating work. This is an opportune time to learn more about Beth, since she will present a lecture, Linen Conservation, at the WGM meeting on April 13 at 7 pm.

Beth McLaughlin received a Bachelor of Fine Arts summa cum laude in Textiles and a Masters in Fine Arts from Ohio University. After she finished her coursework she felt the need for some “real-life” experience before launching on her plan to teach art history and studio arts at the college level. She received an internship at the Biltmore Estate to catalog books, partly because she worked in a library as an undergraduate. During her tenure at the Biltmore, she discovered her passion for textile conservation.

Beth McLaughlin received a Bachelor of Fine Arts summa cum laude in Textiles and a Masters in Fine Arts from Ohio University. After she finished her coursework she felt the need for some “real-life” experience before launching on her plan to teach art history and studio arts at the college level. She received an internship at the Biltmore Estate to catalog books, partly because she worked in a library as an undergraduate. During her tenure at the Biltmore, she discovered her passion for textile conservation.

When Beth started her career in Minnesota in 2005, she worked part-time for the Minneapolis Institute of Arts (MIA) and part-time for the Midwest Art Conservation Center (MACC). She started her own business in 2010 and continues as the contract textile conservator at MACC. Still, much of her work there is focused on MIA artifacts. Beth appreciates being close to MIA and so many of the objects she has restored. “There’s something about being able to keep in touch with “family.””

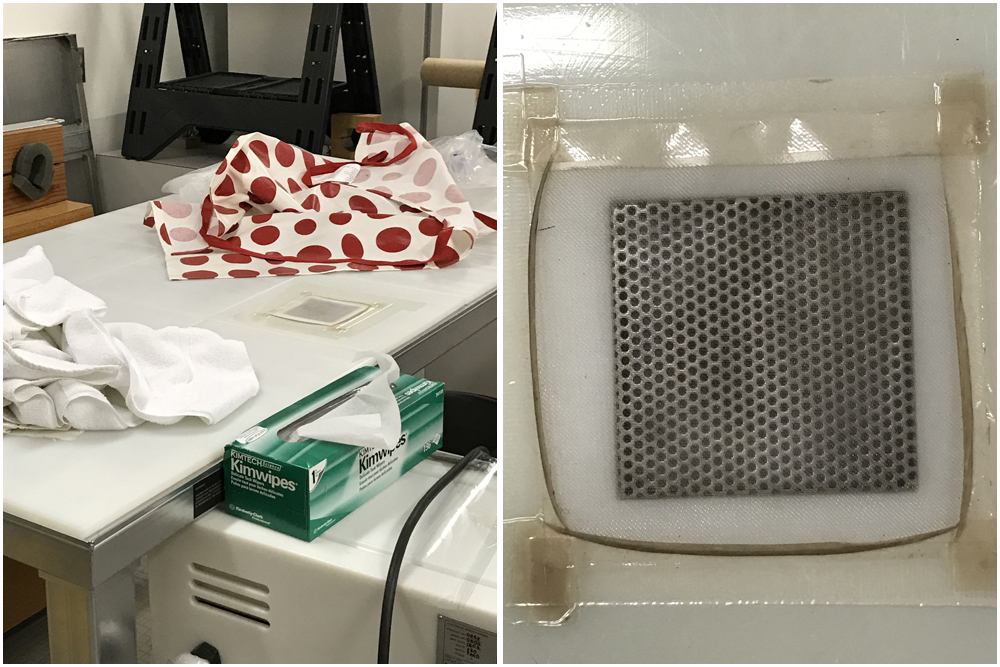

Beth’s high-tech conservation lab is in the basement of MIA—clean and white and well-equipped. A large table supports textiles laid flat at working height. The entire back half of the room is composed of tile flooring on which wet cleaning can be done, with a slight slope for draining. A long steel cadaver sink is at the back. Her favorite piece of equipment is a suction table to treat small areas on textiles. Even if a large textile can’t be wet-finished, it can be laid on the large table with the soiled area positioned over the mesh area, allowing close work. Flexibility is key; the tables are all on wheels and can be combined as needed for large items.

Keeping a healthy work environment is important. The sophisticated air handling system allows octopus-like tubes to be situated exactly where the suction of solvents or dust is most needed. Some textiles that come to the MACC are in poor condition; they are bagged and held in an interim area until Beth has inspected them and ensured they won’t be bringing pests into the conservation area.

Keeping a healthy work environment is important. The sophisticated air handling system allows octopus-like tubes to be situated exactly where the suction of solvents or dust is most needed. Some textiles that come to the MACC are in poor condition; they are bagged and held in an interim area until Beth has inspected them and ensured they won’t be bringing pests into the conservation area.

What’s been handled in the lab lately? A pile rug in a pattern by Juan Miro, owned by an individual, was cleaned and had just been photographed. An 1850s Navajo serape was ready, and will soon be on display at MIA. An elaborate Native American fire bag for flint, sometimes called an octopus bag because of the dangling tentacles, was also waiting in a glass case. Beth worked on an 1830s military costume, padded on the front, from a museum in Wisconsin. She had been asked to make a pattern from the uniform. It was interesting to see the relatively diminutive size of the uniform, to fit a probably normal-sized man of the nineteenth century. Beth said, “I get to touch such wonderful objects.”

Beth is the sole textile conservator. Thinking of the wide variety of challenging and ever-changing conservation problems she faces, I asked who she turns to for help. The various specialists at MACC gladly help one another. If Beth has an issue with sticky adhesive on an old flag, for example, she might consult with the paper conservator. Other textile experts are helpful, including two professional textile conservators who work nationally but live in the Twin Cities. She also contacts a deep circle of textile conservation volunteers who worked with MIA in the past few decades. They can sometimes fill in facts about the history of objects and their conservation that aren’t found in official museum documentation.

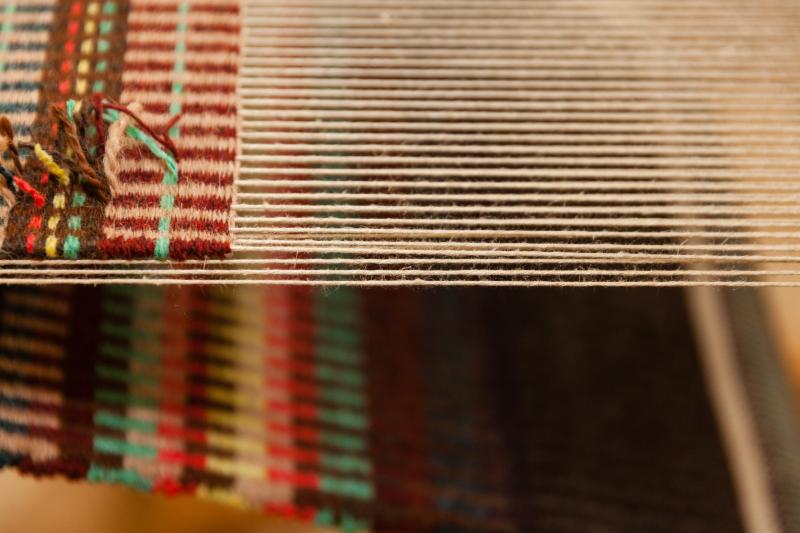

She showed us some handwoven galloons for a tapestry, woven by WGM member Marge Ford Sethna. Phyllis Waggoner helped with them at one time, too. Galloons, the woven hanging strips around a medieval tapestry, are often in need of restoration because of damage by nails over centuries of use. When newly-woven galloons are added to old tapestries they are dyed to match. Beth said that commercially-woven galloons are available, but she prefers the handwoven ones.

She showed us some handwoven galloons for a tapestry, woven by WGM member Marge Ford Sethna. Phyllis Waggoner helped with them at one time, too. Galloons, the woven hanging strips around a medieval tapestry, are often in need of restoration because of damage by nails over centuries of use. When newly-woven galloons are added to old tapestries they are dyed to match. Beth said that commercially-woven galloons are available, but she prefers the handwoven ones.

Beth’s work with a textile is often done in stages. First, an artifact is submitted for verification of fibers and weave structure of all of the components of an item. She evaluates the condition and comes up with a plan for conservation. At that point the artifact may be stored for weeks, months, and some times even years as the museum or individual decides how to proceed, or perhaps raises money for the work.

Beth stressed that her work is quite technical in nature and doesn’t include time for detailed historical research. For example, a fragile flag, with parts in tatters, was laid out on a large table, center stage in the lab. It is owned by an individual but on long-term loan to a regional historical society. Beth determined the fibers and construction of the flag and its repaired areas, information that was used by experts to date the flag and determine its rarity.

The flag illustrates another conservation principle – privacy. While items owned by individuals or organizations are undergoing conservation, public photos are not allowed. It was hard not to share photos of the interesting lettering!

We saw another example of how Beth’s research dovetails with other research, in a chair from the 19th century, owned by a state historical society. Curators conducted research into what fabrics would have been used, historically. They determined that originally, the seats would have been switched out from summer to winter upholstery. Consultations between conservators and curators helped determine a period appropriate option, a soft leather. Beth will do the upholstery—showing the wide range of her talents.

We saw another example of how Beth’s research dovetails with other research, in a chair from the 19th century, owned by a state historical society. Curators conducted research into what fabrics would have been used, historically. They determined that originally, the seats would have been switched out from summer to winter upholstery. Consultations between conservators and curators helped determine a period appropriate option, a soft leather. Beth will do the upholstery—showing the wide range of her talents.

There’s a term for the conservation work done at the MACC. Beth explained, “We’re bench conservators We essentially work at artist’s benches doing conservation. We don’t have time to do deep research.”

Beth joked that “textile counseling” is a part of her job; a frequent phone call she receives is, “I just got this and it needs to be cleaned.”

“Well, why do you think it needs to be cleaned?” Beth begins her response. Because we all wear clothes and use textiles on our beds and tables, and throw them in the washer to be rid of the faintest spots, it’s hard for many people to switch to a conservation mindset. Beth added, “With old textiles, you have to get rid of your twentieth (and 21st) century standards of cleanliness.”

Vacuuming a textile is one of the best conservation methods, though it needs to be done with care to avoid damaging the fibers and fabric. “How do you handle the things that are precious to you, like your needlepoint chair? You have to pay attention to the things you are vacuuming, see the effect of suction on the fibers. It’s an intimate procedure. Some of the techniques we do today are the same techniques that were used for conservation in the 16th century.”

While Beth may not recommended wet cleaning for some textiles, it is often warranted. For example, a tapestry might be too brittle or “crispy” to allow repairs unless it is wet cleaned. You need to remove the acidic components built up from pollutants such as nicotine, to reduce the speed of degradation. Textiles in rooms act as filters, and rugs, of course, are even more disgusting, Beth noted. She does dye-fastness tests ahead of time, and if dyes are not fast, the objects can’t be wet finished.

During our conversations, Beth frequently referred with admiration to the conservation work of her colleagues at the MACC. “You are constantly learning. I could never have learned this all in school.” She is also energized by working on exhibitions at MIA,. On the day we visited, she had just returned from the Walker Art Center, where she has been helping with the Merce Cunningham exhibit. They had a last-minute issue with a costume on display. We are lucky to benefit from Beth’s work with MIA and other local institutions, and future generations of textile lovers and researchers will benefit from her careful research and restoration work.

On the main page of the Minnesota Art Conservation Center website, there is a link: Click Here for 24-Hour Emergency Response. We are in great hands knowing that textile emergencies will go right to Beth McLaughlin.

Beth McLaughlin and Phyllis Waggoner admire a recent tapestry acquisition at MIA.

More on Beth McLaughlin’s work and background: Textiles Conservation